Alexander Kégl was born in a landowner family. The origins of the family can be

reconstructed as follows.

1According to the surviving documents and genealogical

sources, the family had two lineages, whose relationship in the earliest period

is not clear. They were ennobled in different times: the

Kégly lineage in 1623 by Emperor Ferdinand II, while the

Kögl lineage in 1762 by Empress Maria Theresia. This is also the reason of

the differences of their coat of arms.

2 Nevertheless, in the 19th century the two lineages professed their

relationship, at that time both of them using the name form Kégl (or rarely

Kégly). The family of Alexander Kégl belonged to the Kögl lineage, as it is

attested by

the coat of arms on his tombstone.

The marriage of János Kégl and Éva Farkas,

contracted on 8 January 1806 in Felsőpakony, was blessed with 17 children.

3 The eleventh of them was Sándor’s father, also called Sándor

(Alsópakony, 5 February 1825 – Szentkirálypuszta, 14 August 1905). He had from

his marriage with Terézia Jeszenszky of Nagyjeszen

4 (Délegyháza, 3 March 1838 – Szentkirálypuszta, 4 March 1894)

contracted on 14 June 1860 five children:

Mária (Szunyogh, 1 May 1861 – Pusztaszentkirály, 13 January 1874),

Sándor (Szunyogh, 1 December 1862 – 28 December 1920),

János (Pusztaszentkirály, 1 January 1865 – 15 October 1925),

József (Pusztaszentkirály, 19 June 1867 – 8 February 1874) and

Teréz (Tessa) (Pusztaszentkirály, 26 July 1869 – 28 December 1920). Only

three of the children survived to adult age, Mária and József died in smallpox.

Sándor, János and Teréz were loving and loyal brothers. None of them founded a

family of his/her own.

We do not know much about

Alexander Kégl Sr., but it is certain that he was also an educated person,

speaking several languages and interested in intellectual activities who

supported the scholarly career of his son. The center of their estates was

Pusztaszentkirály near to the village of Áporka in Pest-Pilis-Solt-Kiskun

county. Although Sándor and Teréz were also engaged to a certain extent in the

management of the estates, after the death of their father this was mainly the

competence of their brother János.

Similarly to his brother,

János Kégl also pursued his

studies as a private pupil, and then he read law at the University of

Budapest. In 1889, during the Persian journey of Alexander Kégl, János did his

one year’s military service at the hussars. Their father reported in a letter to

Sándor about his service like this: “Jani is healthy. He hopes for a promotion

to corporal by Easter, and he even considers his officer’s promotion as sure by

the end of the year. His superiors love and also appreciate him. I have heard

them speaking among themselves that they believe him to become the best horseman

among the fellow hussars.”

János loved his profession, and he gave

a long account of his affection for jurisprudence – which, in his opinion,

was not equal to practical law – to his brother. He also published several

titles in this subject (Az

ági öröklésről [On collateral inheritance];

Az öröklési jog reform kérdései [Questions of the reform of the

law of inheritance]). Besides he was engaged for all his life in

agriculture. He was especially interested in horse-breeding, and took much care

of

the family estate. At his death in 1925 he left behind an estate of about

230 hectares, which also included a model dairy farm and pig farm.

In his

last will written on 14 January 1925 and complemented on 30 September he

left his estate on the State with the condition that they would establish there

a stud farm within a year. This was the beginning of the famous Hungarian Royal

Stud Farm of Pusztaszentkirály. He also established a number of foundations, for

the renovation and enlargement of the Catholic church of Pereg,

5 the building of a seat for the credit union of Áporka, and for the

books and school equipments of the poor children of the elementary school of

Áporka.

Teréz, the youngest of the three was a person endowed with great

intellectual skills and a talent for languages who could be an intellectual

partner of his eldest brother. László Gaál, a student of Kégl in his necrolog on

his professor

6 wrote about her like this: “He also had an adequate company in the

person of his sister who spoke about ten European languages … and with whom he

could discuss his scholarly subjects and practice languages. Most probably his

essays on English subjects were also written on her inspiration.” According to

the witness of the bequest, Sándor and Teréz simultaneously used

the same notebooks, and Teréz also took part in the formulation and copying

of the English essays of his brother. We do not exactly know how they shared the

work, but Sándor’s

treatise on Shelley, published in 1913

7 was left to us

in the hand of Teréz, most probably dictated and then corrected by Sándor

himself.

Teréz Kégl was also an author of essays, including one on

Újabb angol regények [Contemporary English novels] and a

“novelette” entitled She who loved much.

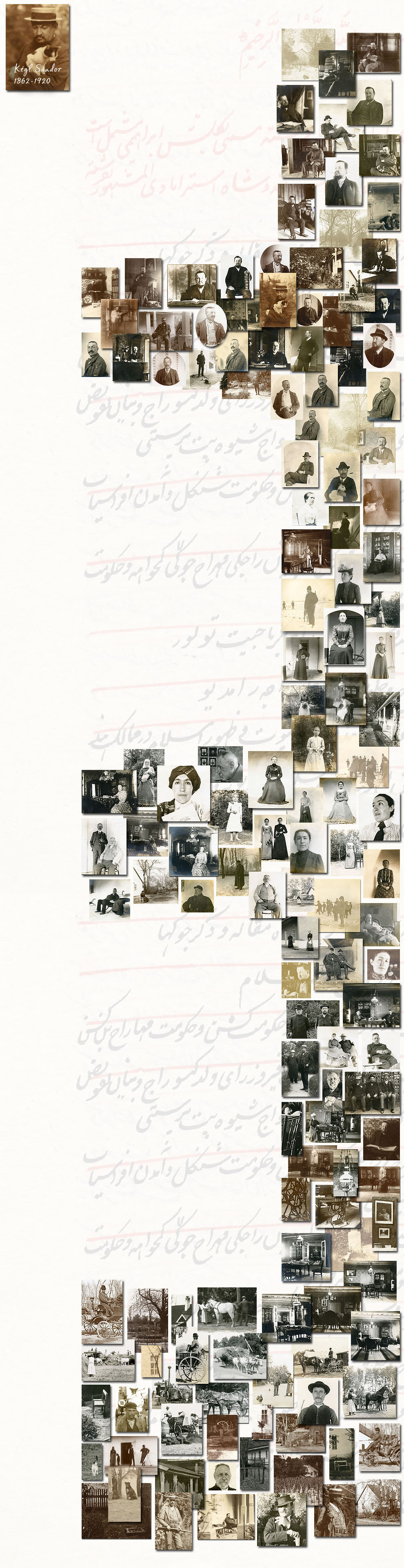

Besides literature and languages, the wide range of interests of

Teréz also included photography. She was an enthusiastic amateur photograph. Her

article written on her experiences of photography was published on 24

December 1906 by the journal The amateur.

8 Most probably she was the author of most of the photos left to us

on the family and the estate that are presented here (MTA Dept. of Manuscripts,

Ms 5075), as she herself wrote that her camera “is devoted to the family stove:

this beautiful bright lens is the illustrator of the home”.

The love of music permeated all the family. They were

serious clients of the most important record shops in Budapest. Sándor and

Teréz had their special notebooks where they

noted down the texts of their favorite opera arias.

Teréz Kégl spent her days in Pusztaszentkirály, in the circle of

her extremely educated, much-reading family members speaking a large number of

languages. Besides them she had no adequate intellectual company. Her letters

reveal that in the absence of her brothers she felt being “in a Babylonian

captivity”. It is no surprise that at the sudden death of her brother she also

saw the sense of her life being lost.